Memory is The Images in Mind

It is nearly impossible to separate cinema from history and vice versa. Since its conception, camera has made it possible to capture various events so that people can see them again in the future. People can identify history in the mediums that attempt to represent it. On the other hand, cinema is a medium of history representation as well as the history itself; it is both the event and the act. In this case, tracing a monumental cinema work, such as the film Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September (roughly translated as Betrayal of the 30 September Movement), which tells a historical event, is also a search for the history of cinema itself; how the image moves from one medium to another until it becomes a reality beyond the film itself.

Recording by Watching

Initially, as part of a generation who did not experience

the historical events narrated in Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September and

did not live in a time when watching it was a mandatory act, I thought this

film would not trigger a familiar memory to me. But I was wrong. The fact that Pengkhianatan

Gerakan 30 September has been shown annually on television and is an

official state production makes certain aspects in the film's narrative becomes

part of normality in the society. Thus, even though no specific form in the

film is familiar to this new generation, at least a certain standard form of

behavior in society can be recognized in it. Because in a long period of time,

through the educational process of various social institutions—family being one

of them—these aspects are continuously reproduced and become a general

knowledge encoded in our body.

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

Arifin C. Noer's film tells the story of an incident that occurred on September 30, 1965, in which the seven generals who were accused of attempting a coup against the president at that time—Soekarno—were abducted and murdered. The story is divided into two parts. The first half consists of the background of the events and the events themselves. This is followed by the second half titled "Penumpasan" or "Eradication". This docu-drama genre combines newspaper archives, photos, and recordings with images made from the director's translation of the state's archives. By using fiction as a method, the director puts history as a flashback of people's memories to be re-witnessed by the audience.

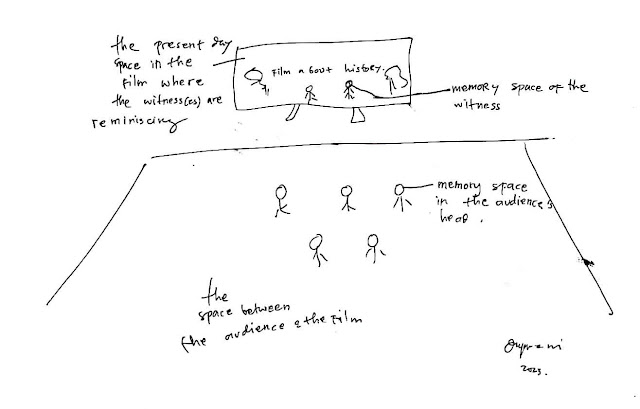

In a scene where one of the witnesses to the September 30 incident attempted to locate the abduction and murder site, the camera presents flashback images along with the sound effects to display the murder scene once again. The witness's reality returns when the camera shows the trees, the land, and the current location of the murder (in the film). The sequence of images and sounds seems to produce a thin separator in the abstract spaces that appear while the film is being screened and watched: memory space of the witness, the present day space in the film where the witness is reminiscing, the space between the audience and the film, and the memory space in the audience's head.

|

| Schema of the memorial abstract spaces that appear when the film is being played and watched. |

Through the eyes of the camera, the eyes of the audience can

also see an event even though their body was never present at the location and

time when the incident occurred. It was through this incident that the audience

recorded the events that they had never experienced. Biographically, a

vocabulary from the film has become a part of the audience's memory. The

vocabulary can be a choice of words that are later used to articulate or

translate experiences, either directly related to the experience in the film or

completely different. Of course, this act of remembering is very personal. Each

person with their existing recordings, whether they are recorded using the eye

of the camera or biological eyes, will mutate their memory into anything they

want according to the impression they get.[1]

I personally remember this film as a depiction of family

story in the late 1980-1990s where feminine passivity and an established modern

life were desired—a legacy of values in the form of cinema. An ideal that moves

from one family to another through cinema and TV. This impression is triggered

by how the domestic space of families in Indonesia—from poor, middle-class,

wealthy urban families to poor rural families—is presented between scenes of

political meetings, military training, and abduction to fill the fabric of film

construction.

A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September”

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

In a scene depicting moment of horror and loss in a simple rural

family setting, the film starts with the cheerful atmosphere of a kindergarten

in the city featuring Ade Irma Suryani (Keke Tumbuan), followed by the scene of

a boy and his mother wandering in an empty station. The sound of the

kindergarten chorus fades into Sundanese music, the visualization of the boy

and his mother leads to the identification of a person who does not come from

the city. Suddenly, the scene shifts to the extreme close-up shot of a man's

eyes and mouth (the same type of shot appears several times in this film to

portray the ambitious D.N Aidit, played by Syubah Asa).[2]

The scene is then followed by the murder of a man in the village and the

mourning atmosphere of the wife and child he left behind. The importance of

father's masculinity is emphasized precisely by his death. The scheme that

appears at the beginning of this film appears repeatedly in the middle to the

end of the film in the form of the abduction and murder of the generals.

The bereavement experienced by that boy (named Urip) and his

mother found its redemption through their migration to the city. The initial

gaze of the city in Urip's scene is the gaze of the industry that appears in

the form of sound and railroads. This feels even more empathetic in other

scenes about Urip when a low-angle shot captures the top of Monas then closes

up on Urip's face, who seems to be very thirsty as if he want to gulp down the Monas.

More than just a scene trying to pinpoint a location, it reminded me of a

situation where people from the rural area arrive at the city and immediately

see what they usually only watch on TV: amazed and full of desire. Of course,

it is difficult to deny that the shape of Monas, which resembles a phallus, is

a sign of masculinity and perhaps modernity.

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

Unlike Urip, a girl from a middle-class family who is

afflicted with economic difficulties appears many times in this entire film,

but never speaks at all. She is constantly moving and working, allowing her

father's monologues and dialogues to flow uninterrupted without ever speaking

or intending to do so. She moved broadly and clearly as if her path of motion is

a habitual trajectory that her body had completely memorized. The same

choreography is repeated during the next appearance of the girl. She, within

the framework of a family, is present through her work activities only. She is

described as a subject that is constantly moving but also remind silent at the

same time. To paraphrase Hsu Fang-Tze, an academic from Taiwan, she is

described as silent letters in English—they are present but unuttered.[3] Her

silence, during endless conversation between her father and brother, is like

the obedience of a moviegoer in a screening room that is conditioned to be

quiet. Its presence is needed as a validation of stories and narratives but is

not intended to tell stories, at least until a time when cameras are not only a

luxury owned by certain groups.

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

Film, in this case, is a representation of a set of social,

cultural, economic, political and technological references that manifest in the

eyes of the camera. Therefore, it is also a vision of ideology, identity and

perception that organizes everything it records into a unified image of the

world that evolves into an independent world of images, which is communicated

to the public through cinema. Its ties to the reality that it previously captured

become looser and could even be severed to form a new arbitrary relationship.

The world of images that works collectively in film is history itself, in its

own truth—and through massive amplification, it may become a regime. As in the

grammatical system, words are arranged into sentences and resonate information

through receptors to the mind and deposited in mental loci—so didactic that it

can easily be reflected through the prevailing bodies.

In a choice of cinema language that collides with the reality of documentary and fiction, the fiction of the entire world of images becomes apparent. A scene, almost at the end of the film, specifically in the 258th minute, a camera appears focusing on the audiences of the film sitting across their screen. The colored pictures that have been present since the beginning of this film are immediately replaced with black-and-white pictures up until the film’s end credit scene. Although the discussion in this article refers to the long version of this film, which in certain sequences is different from the short version, this color issue appears in both versions. I conclude that the issue regarding camera and coloring is Arifin's choice of aesthetics, which may also remind us that this 272-minute moving picture is indeed a film.

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

Memory is The Images in Mind

I once spoke to a friend, that Harun Farocki's films are not

an easy and common genre to watch. However, it is precisely these two things

that give us a sense of eeriness when watching the film, inviting the audience

to re-think about similar pictures that we see every day that has been so

common which makes the concept settles in our heads. On the other hand, Farocki

films also seem to offer a method to reflect on how images, like words, are

also an apparatus that is constructed and produces information, knowledge as

well as subjectivity.

In his works, Farocki often indicates how images can no

longer be presented as mere representations, but also as criticisms and

reflections on the concept of representation itself. When reading the synopsis

of his films—some of which I have not watched due to limited access—from 1966

to 2013, you can see how Farocki explores images not only on one medium of

representation. He tries to dissect aesthetics from painting, photography,

video, film, to digitally produced images in the form of games. Some of Farocki's

works, such as the Parallel series (2012-2014), the Serious Games series

(2009-2010), and Inextinguishable Fire (1969), demonstrate how the world

of images is strongly connected to how humans perceive and respond to events in

their surroundings.[4] The images he presents not only interpret certain sign

systems but also 'perform' something to physical reality outside the film. They

are—almost always—part of an operation.

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

The use of cinema as a medium for the inscription of certain knowledge and subjectivity by the state was quite intensive in Indonesia during the New Order era under the leadership of President Soeharto from 1966 to 1998. At that time, motion picture production was one of the most important aspects of the state. Starting in the 1950s and continuing to the New Order era, government departments and military groups funded a number of films as a propaganda medium. This continued to be done openly when the State Film Company (PFN) in 1978 began producing period piece depicting historical events from various eras in order to emphasize the sense of nationalism, and also to create a cult of personality. Entering the 1980s, local film censorship was also tightened with the introduction of code of ethics for film production, which is generally concerned with how to preserve Indonesian morality and ideology. This tight curation also occurred in television where no private TV station was allowed until 1989. As such, the aesthetic choices seen by people at that time were extremely limited.

|

| A scene from “Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September” |

The film Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September, which

was produced by PFN, was screened not only in cinemas but also in schools, outdoors

and television. According to the stories I've heard, since its release in 1984,

this film was broadcasted once a year on TV and must be watched. Due to the

limited number of channels for pictures at that time, this film became a

didactic reference to the 1965 incident, which is said to have actually

happened in historical records.

However, all of these come to an end after the fall of Soeharto's

rule due to massive movement organized by students, the economic crisis, and

demands for a more democratic system. In 1998, the screening of the film Pengkhianatan

Gerakan 30 September on TV was stopped and for a long time, this film

seemed to just disappear.[6] When I was an elementary student, I remember one

of my teachers said that I should not watch this film because it's not right. To

this day, I’m not sure what she meant by ‘right’. But still, her advice prevented

me from watching this film until I was no longer a child and decided to watch it

not for historical reference either. I found the film in the cloud via YouTube,

in 217 minutes duration, with poor picture quality due to the digitization

process from VCD/DVD.[7] In line with this film which disappeared and only

appeared with terrible quality, debates about the truth of history also emerges

with its own fragmentation, along with other aesthetic choices that are also

starting to widen. The digital era is increasingly expanding these choices and

historical references are no longer singular.

|

| Some search results of the hashtag #nobarg30spki |

In an instant, this film found a new habitat and ecosystem.

From celluloid, to TV, to VCD/DVD, to YouTube, to laptop then back to TV again

and then on Instagram, and possibly on other social media as well. As a social

media platform that is highly visual, Instagram has specific aspects related to

the use of mobile phone cameras as a means of producing spontaneous everyday

images—although nowadays Instagram visuals are not exclusively produced by

mobile phone camera and probably have experienced professional editing process.

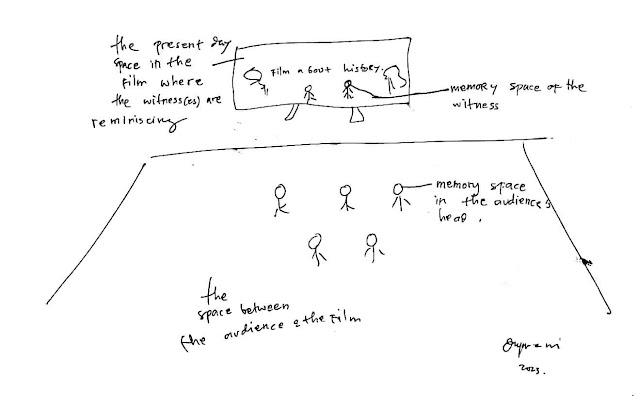

Its life on Instagram as medium continues to the next year, just like its appearance on TV in September 2018. However, unlike its appearance on TV as a mere film, on Instagram it comes with many interpretations. There were 30,789 uploads marked with the #g30spki hashtag,[10] but only few feature the film. Most of the uploads were scenes of school play, diorama photos of the September 30 Incident as well as various posters and quotes. However, advertisements and other things that often have nothing to do with this film are also embedded with the same hashtag and, as a result, appear in the list of photos or videos uploaded with this hashtag.

|

| Some search results of the hashtag #nobarg30spki in 2017 |

|

| Some search results of the hashtag #nobarg30spki in 2017 |

|

| Some search results of the hashtag #nobarg30spki in 2018 |

This is different from the hashtag #nobarg30spki which specifically refers to the activity of watching the film Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September. At around 2,451 uploads with this hashtag as of September 30, 2017, I managed to find photos of the atmosphere during the communal film watching activity and also lots of selfies. However, the film watching’s participants were not the only one who took a selfie of themselves, but also those who need popularity and affirmation, such as politicians, celebrities, online shops—all of them used this hashtag to publish their selfies as well as to sell their economic commodities. At this point, Instagram is a medium of self-propaganda for its users. People seem to be more interested in photographing their presence at events that they consider important today rather than dealing with the history of these events in the past. Thus, #nobarg30spki on Instagram is an event as well as an action to become part of historical record.

However, there is a significant shift in the contents uploaded in 2018. The number of uploads as of November 5, 2018 at 6:14 WIB were 2,567 uploads—an increase of about 100 uploads.[11] Most of these additional uploads have nothing to do with watching the film like last year. In fact, most of them are not even produced by mobile phone cameras, because they tend to be posters, videos, quotes or even advertisements. This is understandable given the year 2018 was close to the election year of 2019, and it makes the political context of the film becomes more prone to be used as political tool. Nevertheless, the enthusiasm of Indonesian Instagram users in 2017 who wanted to take part in the historical event of nobarg30spki (watching together g30spki), where thousands of photographs about #nobarg30spki were uploaded to Instagram in a matter of days, can no longer be seen.

|

| Some search results of the hashtag #nobarg30spki in 2018 |

At the end of the day, can we consider those uploads as a

form of agency from the people who use cameras to instill new narratives about

past incident? I still have my doubts. For a country that has lived under

authoritarianism, regime does not only exist in the rule of law. It can also exist

in an audiovisual work that can last even after the regime has passed.

Historical events become monumental not always because of their big moments but

rather their resonance and exposure to people that change the way the people

respond to the experience of another event. That’s what makes them crystallize

and gigantic. The memory of the exposure can build a standard of how to look

and act. It becomes a picture that moves in our head, constantly, that we don't

even know how fast it moves and helps us interpret experiences. It is an image

inscription that turns into memory inscription.

* This text was read at the Farocki Now: A temporary

Academy event on 18 – 21 October 2017 in Berlin and has now been edited or

adjusted.

↑1 Eric Shouse in

Feeling, Emotion, Affect from M/C Journal vol. 8, Issue 6, Dec. 2005

http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0512/03-shouse.php

↑2 A more

complete analysis of the aesthetics of Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September and

how it describes its characters and events can be found in Hafiz Rancajale's article

titled “Mari Belajar Bahasa Filem dari Pengkhianatan G 30S/PKI” published in

Jurnal Footage on 1 October 2010, link: https://jurnalfootage.net/v4/mari-belajar-bahasa-filem-dari-pengkhianatan-g-30spki/,

accessed on 7 November 2018 at 16:00 WIB.

↑3 Fang-Tze,

Hsu. When Dead Labor Speaks: Subjectivity, Subjugation and Meta-Cinema.

Forum festival 2017. Jakarta, Forum Lenteng. 2017, p. 9 & 138.

↑4 A more

complete analysis on how the three films communicate ideas about imagination

formed by representative media can be read in an article by Manshur Zikri, Yang

Paralel dari Sang Komandan Farocki, published in Jurnal Footage on 7 November

2014, link:

https://jurnalfootage.net/v4/yang-paralel-dari-sang-komandan-farocki/ , accessed

on 6 November 2018, 21:51 WIB.

↑5 From the

text of Phantom Images by Harun Farocki, translated to English by Brian

Poole. The text was presented at a discussion at ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany in

2003. This text can be downloaded at: https://public.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/public/article/

view/30354/27882, accessed on 6 November 2018, 22:08 WIB.

↑6 “Tiga Tokoh

di Balik Penghentian Pemutaran Film G 30 S PKI”. TEMPO.CO. published on Monday,

18 September 2017 at 07:56 WIB. Accessed on 7 November 2018 at 12:21 WIB

↑7 At the time

this article was written, on October 10, 2017, the only upload of this film on YouTube

was 217 minutes long with poor quality. Using the same search keywords today,

when this article was updated on November 7, 2018, there has been an upload of

this film with very good quality, but the duration still varied. Link https://www.YouTube.com/results?search_query=g30s+pki

referring to YouTube search page, last accessed on 7 November 2018 at 12:29

WIB.

↑8 “Saksikan,

Film Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI di tvOne Malam Ini”. Ansyari, Syahrul. Viva.co.id published

on Friday, 29 September 2017 at 08:12 WIB. Link:

https://www.viva.co.id/berita/nasional/961566-saksikan-film-pengkhianatan-g30s-pki-di-tvone-malam-ini

accessed on 7 November 2018, at 12:23 WIB.

↑9 “Pemutaran

Film G30S PKI Malam Ini di TV One, Karni Ilyas Ungkap Hal Ini”.

TribunPekanbaru.com, published on Sunday, 30 September 2018 08:07. Link:

http://pekanbaru.tribunnews.com/2018/09/30/pemutaran-film-g30s-pki-malam-ini-di-tv-one-karni-ilyas-ungkap-hal-ini

accessed on 7 November 2018, at 13:35 WIB.

↑10 The

Instagram website and my search result can be visited at https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/g30spki/

but the amount and content may continue to change. Last accessed on 7 November

2018 at 19:00 WIB.

↑11 The Instagram

website and my search result can be visited at https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/g30spki/

but the amount and content may continue to change. Last accessed on 14 October

2018 at 00:53.